Wireless Arduino Nunchuk

Written 8-19-19

One of the things that I’ve been meaning to build for awhile is an easily programmable and elegant remote to power random wireless projects I come up with. During our RoboSub electrical team meetings I found out that our PM Mark had used a Wii Nunchuk as a remote for his electric skateboard. I thought that was a really awesome idea, so I kept it on the stack of stuff to build the next summer.

My design philosophy is pretty much the embodiment of “form follows function.” No one is going to use a product that doesn’t work. However, people also like to use products that have a nice aesthetic. The two aren’t mutually exclusive. Usability is also very important because if a product is hard to use, fewer people will use it. That’s why I chose a Wii Nunchuk as the outer shell for my remote. It packs excellent ergonomics, ease of use, and multiple control inputs all into a compact and beautiful package.

Build

At first I wanted to 3D print a Nunchuk and then fit everything inside but my CAD skills aren’t yet advanced enough to make organic looking designs so I ended up buying a cheap Nunchuk off Ebay. Upon taking it apart I immediately began to wonder how I was going to fit a battery inside it. I didn’t have any LiPo batteries small enough so I picked a NiMH AAA as a good compromise of size and capacity as well as being swappable. Then I started removing internal structures to make room for the AAA and cut a hole large enough to fit. Using some springs from the Amazon Dash Button and a 3D printed part, I fitted the Nunchuk with a battery holder, leaving ample room for rest of the electronics.

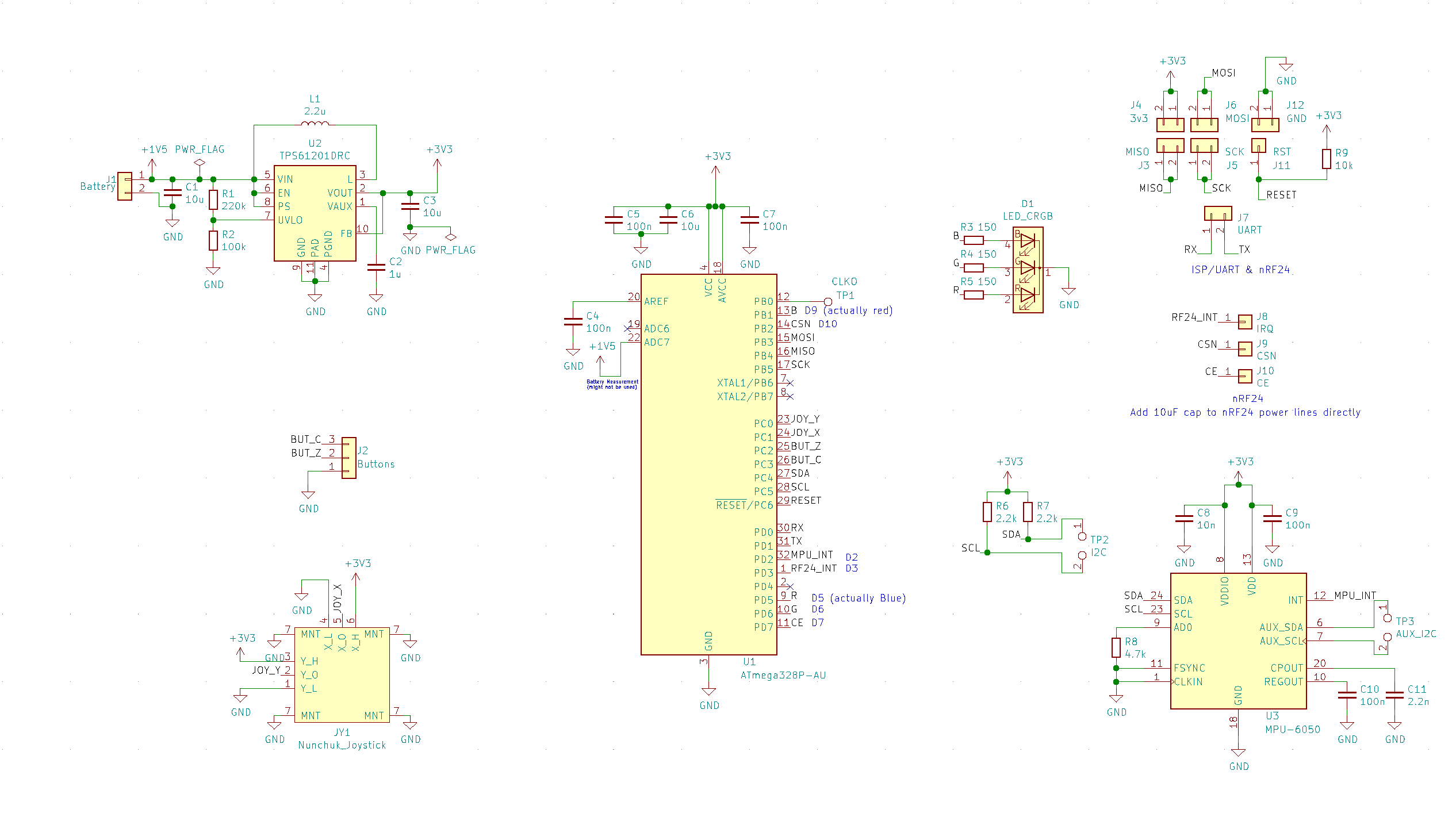

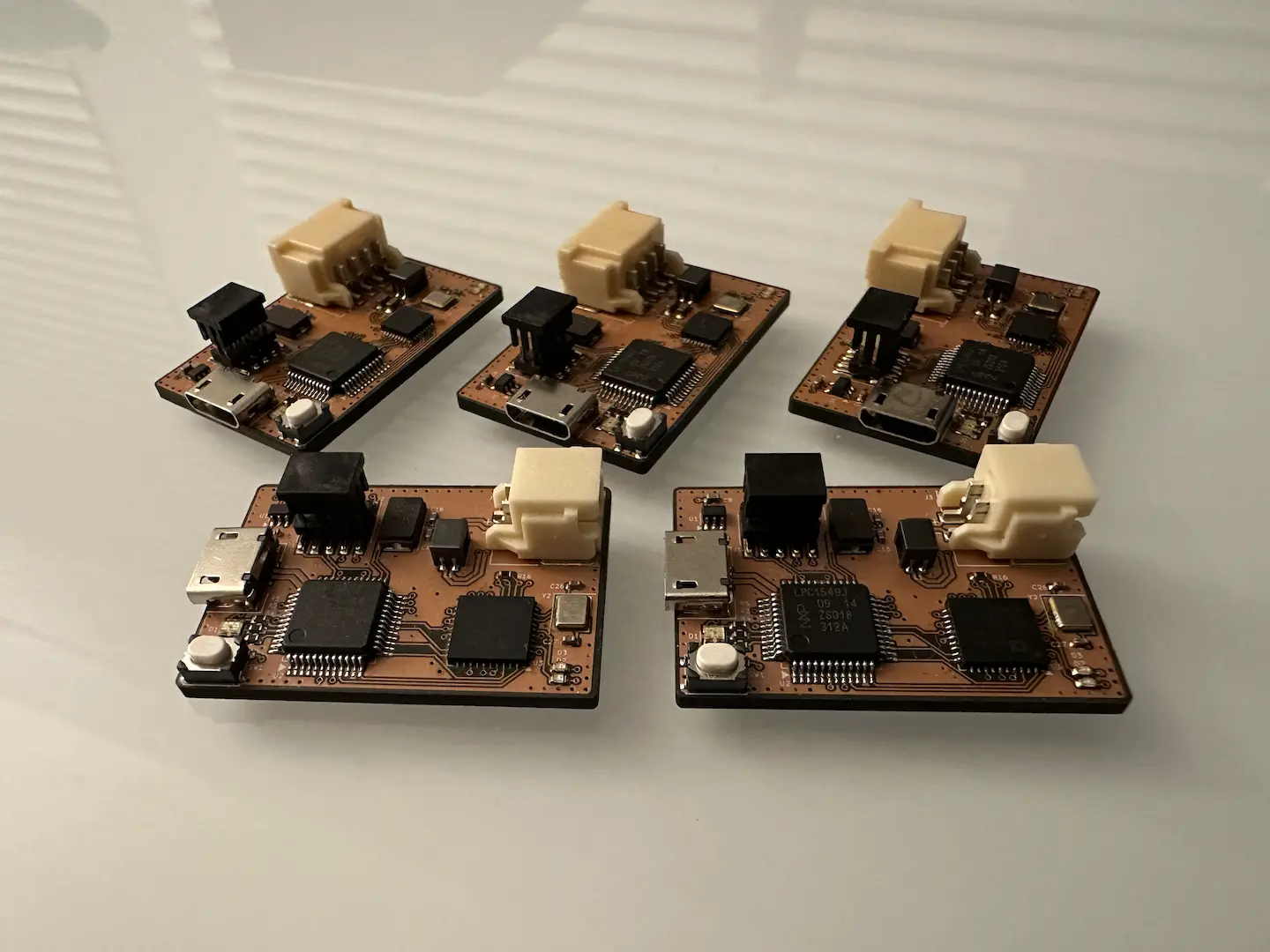

The next step was picking out the features of the remote. I chose to keep the joystick and buttons, but added an MPU6050 and RGB LED. Since I still have a couple left and it’s the most widely supported Arduino microcontroller, I stuck with the Atmega328P-AU. I threw everything into KiCad, where the only part I had to design a schematic symbol and footprint for was the generic joystick.

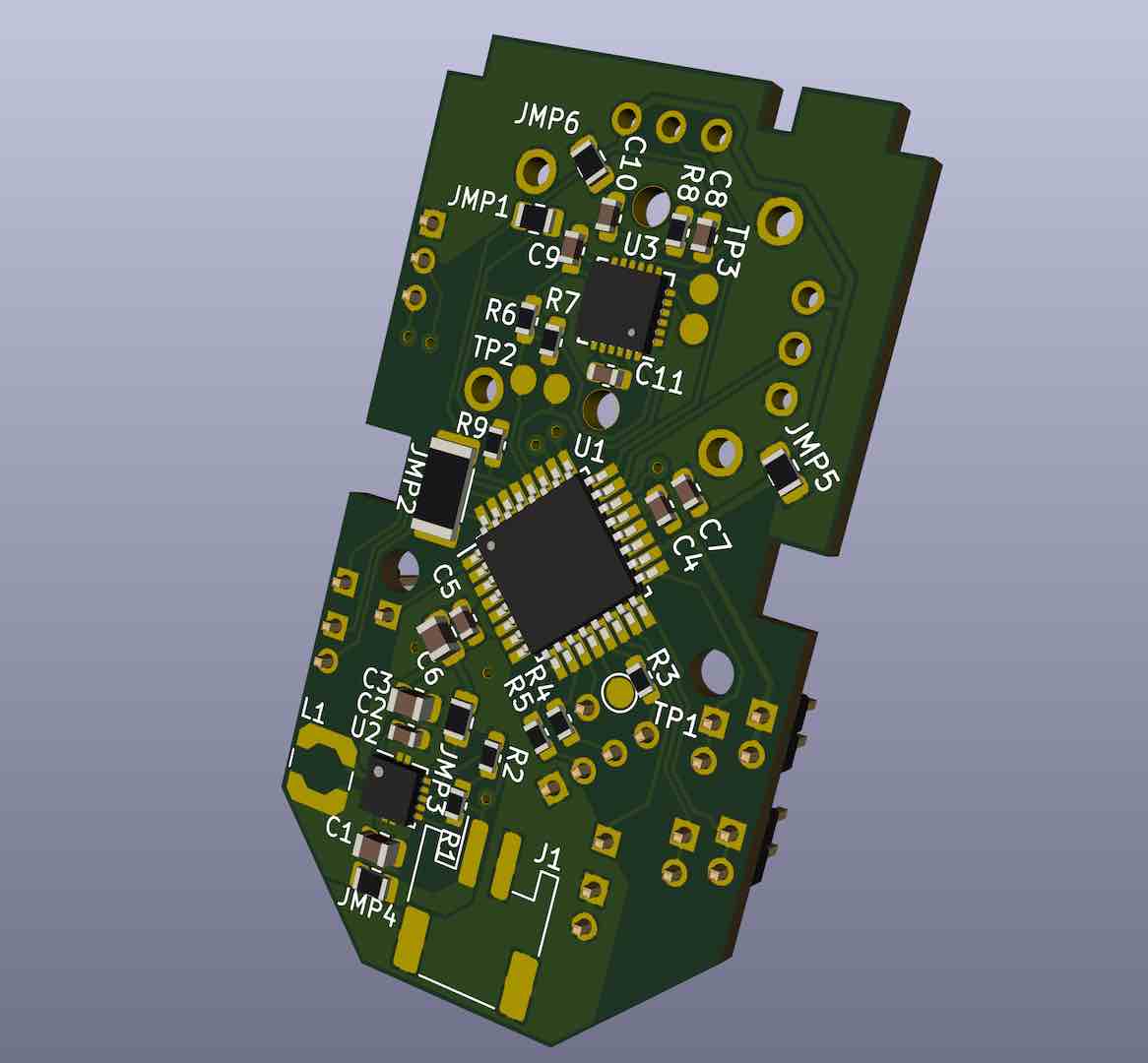

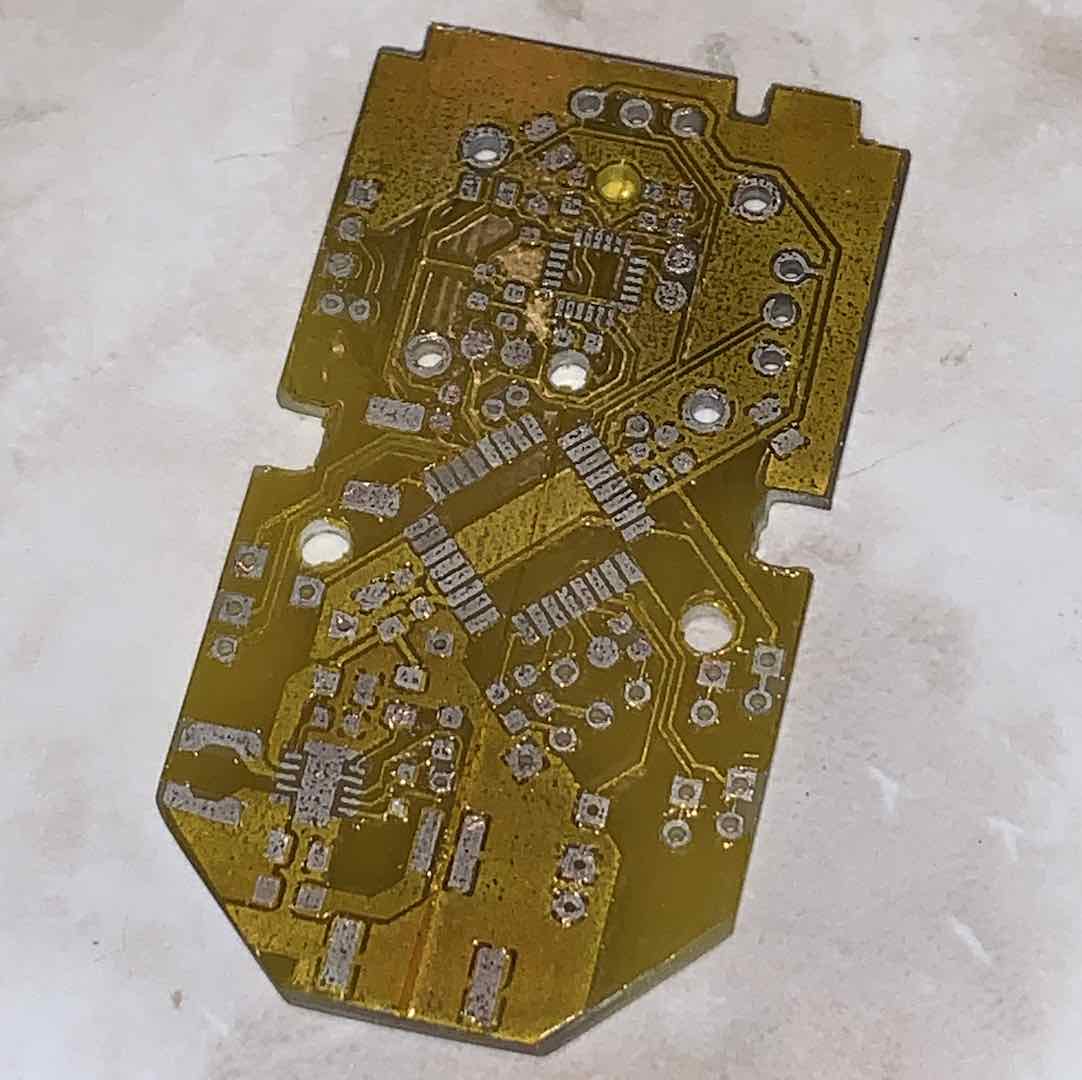

With my trusty caliper in hand and a couple 3D printed tests, I was able to create a board outline that would fit perfectly into the Nunchuk and maximized available area for placing components.

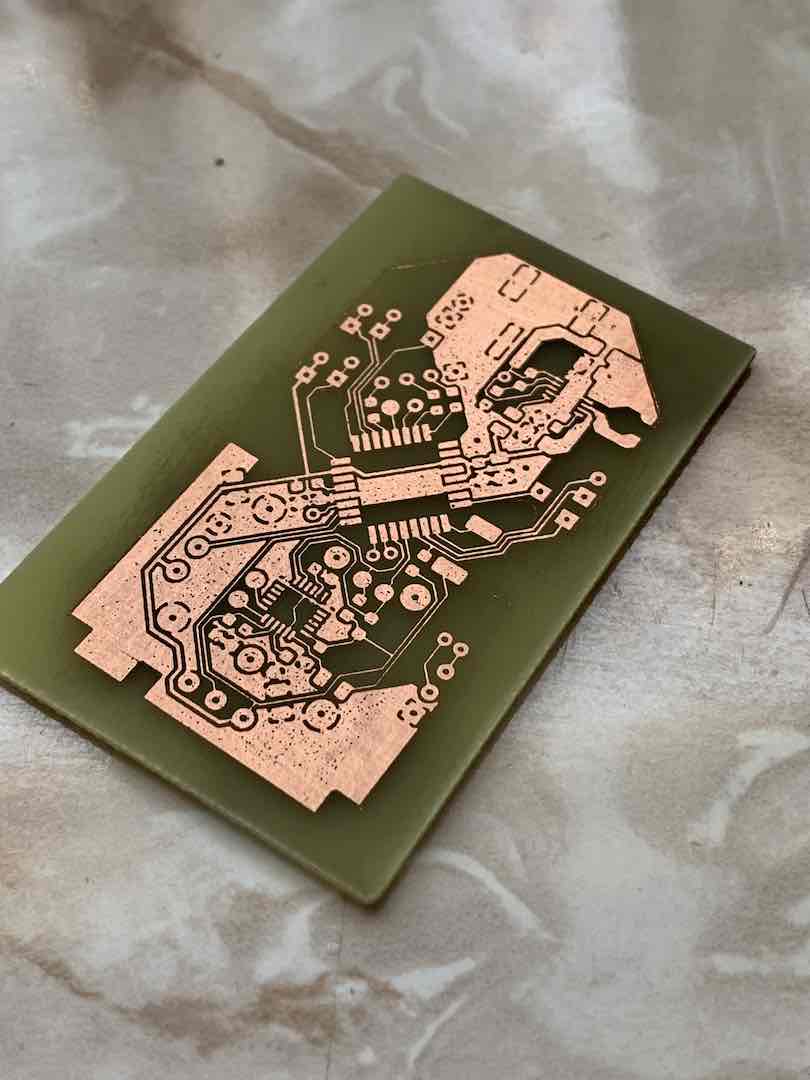

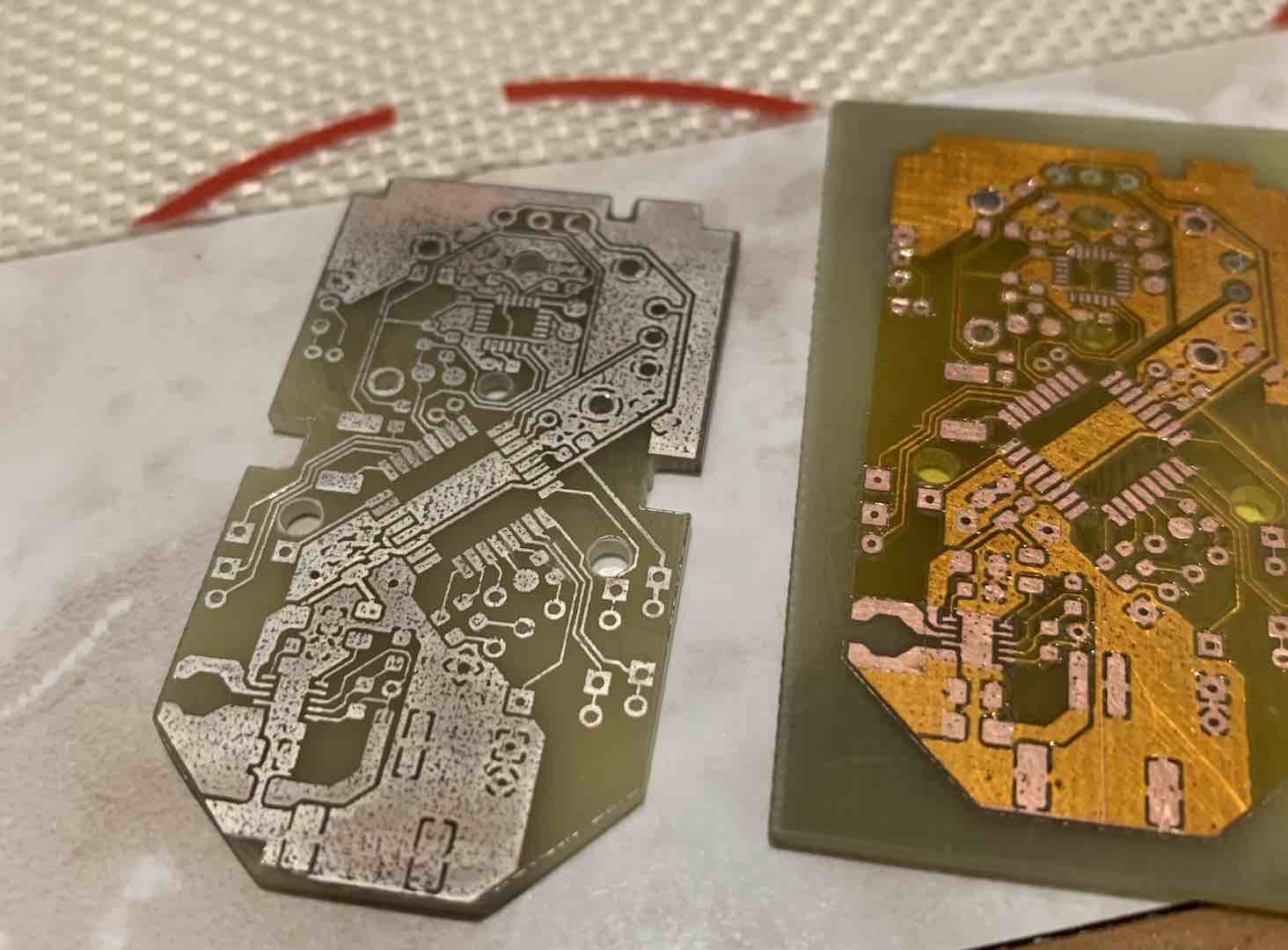

Making the PCB was relatively straightforward, except for the drilling because I didn’t have the right size bits. FR4 does sand nicely, so getting it exactly to size was a breeze.

I even tried making a solder mask using Kapton tape and an X-Acto knife. It worked really well, but is too tedious for me to give a recommendation. The UV cure solder mask I’m working on now is far easier and more effective.

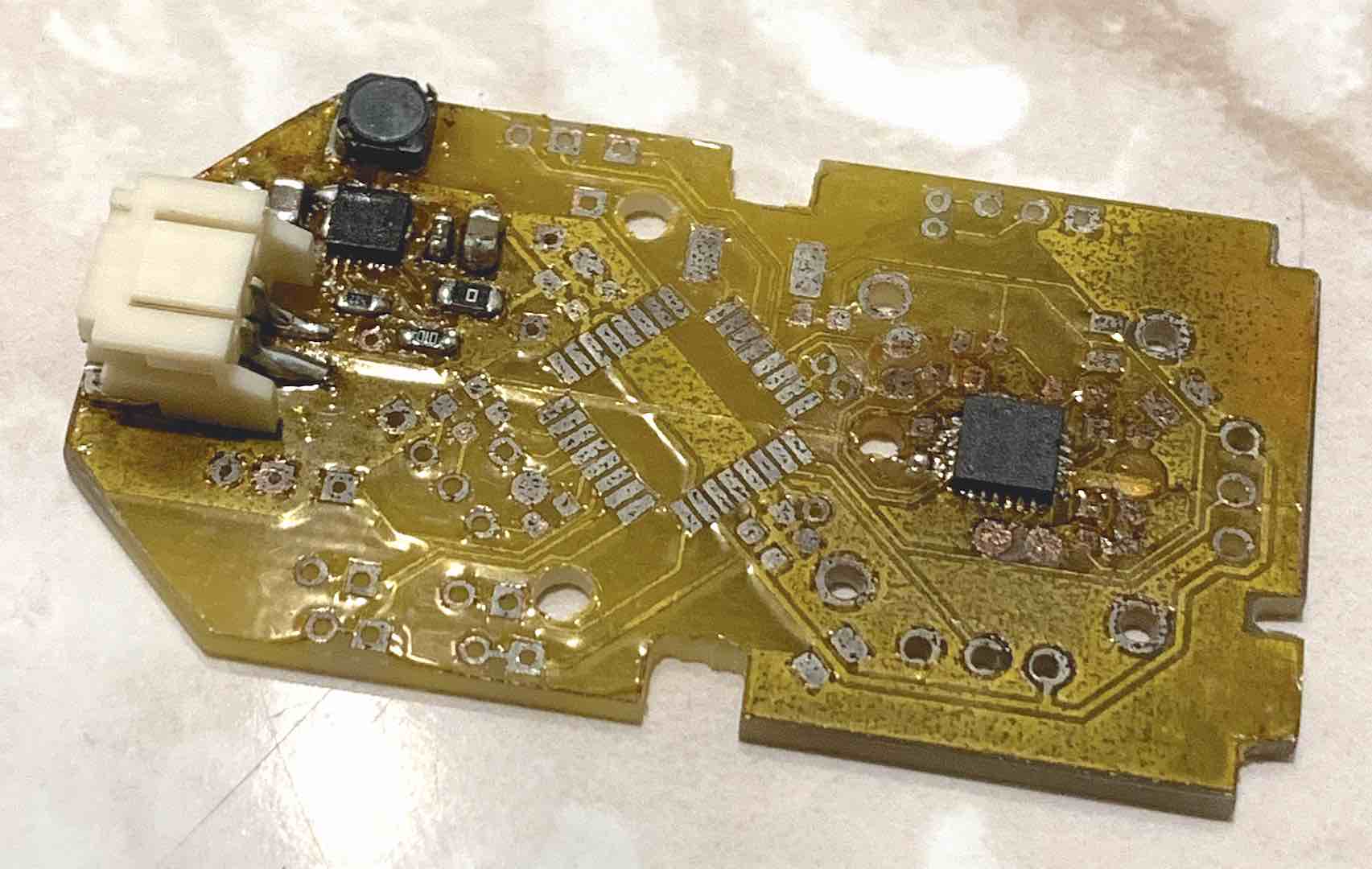

I had to jerry-rig my soldering job because I didn’t have solder paste, but after several reflows, lots of flux, and some of the finest trace repairs I’ve ever done, the board was working.

All the electronics ended up fitting really nicely. I had to add a piece to improve the rigidity of the casing but other than that, the rest of the assembly was clean. I really liked how I routed the RGB LED to the front top and made a custom port at the bottom for programming and serial debugging. There was also quite a bit of room underneath the PCB to fit the nRF24 board.

Programming

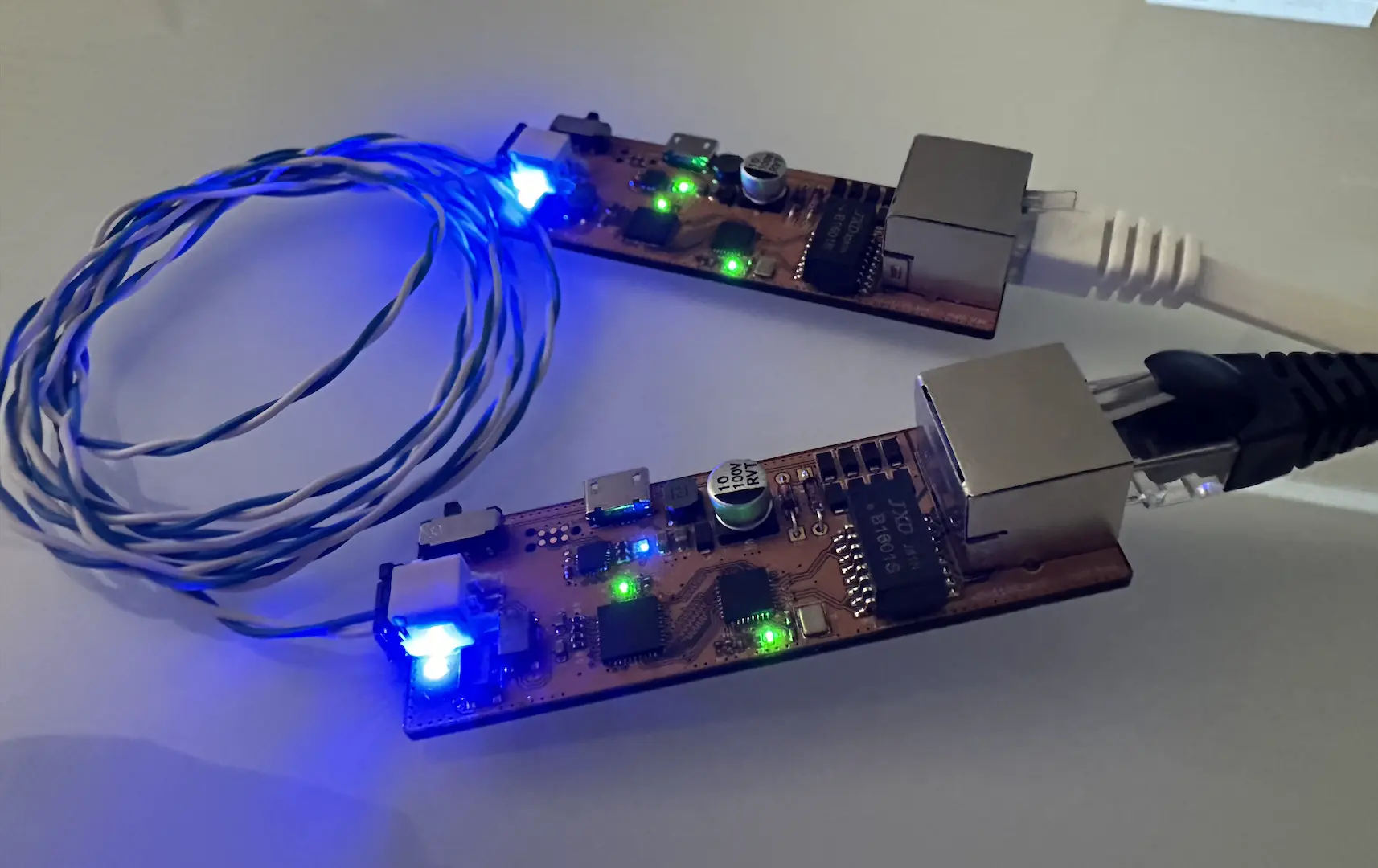

Since I didn’t have a specific project I wanted to control with this remote, I stuck to creating a template that would make integrating it into any project relatively easy. You can find it here. The Teensy I used as a receiver has a little quirk because it uses ARM instead of AVR architecture.

Using a Teensy with the FreqCount library, I first calibrated the internal RC oscillator, setting the OSCCAL register.

Sending the battery voltage in a uint8_t (range is 0-255, which is good enough for a 1.5v AAA) instead of as a float proved a little tricky, but I got it working. analogRead() returns an int which when multiplied by 330 overflows so I had to cast it as a long.

The code for the joystick was a little trickier than expected to get clean because it centers at a point not exactly in the middle of its range so I had to use two different map calls.

The last part was calibrating the MPU6050 and getting it working with the InvenSense Teapot Demo. I used a program I found online to get the gyroscope and accelerometer offsets, using some tape rolls to hold the remote in the proper orientation. I then set the fine gain on the accelerometer so that the measured gravity vector was constant in all orientations.

Since I was heading to Maui soon, I didn’t have much time to do much other than create a really basic demonstration of using the remote as a mouse. I pretty much just used the raw gyroscope values to determine movement and the accelerometer to determine orientation to simulate lifting the mouse.

Overall, as a prototype I’d say this was a success. I’m not sure what the market is for these things but it’d be pretty cool to bring this into production. The case needs rework and I’d probably want to modify the internals to incorporate the nRF24 into the main board and use a 9-axis IMU and add USB programming/debugging but otherwise it’s pretty solid.

Comments