CS170 Final Project

As the finale to an amazing algorithms course, we had to tackle a problem called Drive the TA’s Home. It is setup as starting at a certain node in a graph with a certain number of TAs which all live in unique nodes on the graph. The goal is to find a cycle of nodes to travel through and a list of drop offs that minimizes energy cost. Dropping a TA off at a node makes them travel the shortest path to their home, with an energy cost of 1 per unit distance traveled. Driving along an edge has an energy cost of 2/3 per unit distance traveled. We weren’t looking for an exact algorithm but instead the best approximation we could.

Since the project changes every semester, I made our repo public, which you can find here.

Algorithms

My teammates and I came up with quite a few algorithms in our search for the best outputs to the 949 inputs we were given. We also iterated many times and improved performance a lot along the way. Here’s descriptions of our algorithms, in no particular order. In the interest of time, I’ll keep them short.

Brute Force (brutepython, brutecppLVIII, brutecppCC)

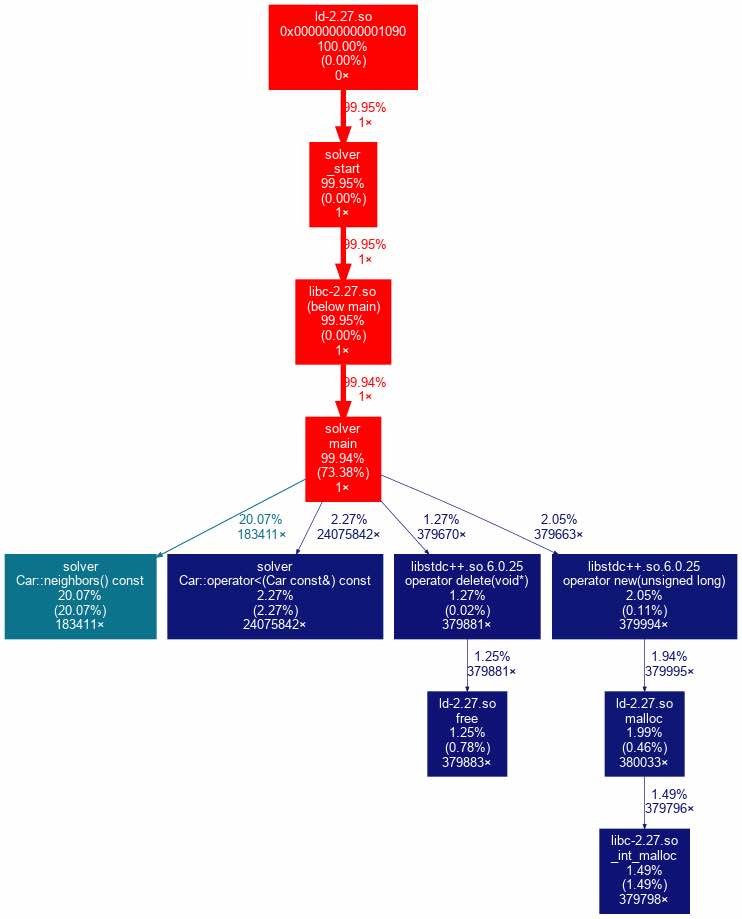

In order to provide a baseline we could compare our other algorithms against, I started by creating a brute force algorithm. To ensure we were finding optimal solutions, I used an object oriented approach with a Car object that has both a location and a set of TAs. We start with a Car at the starting location that has all the TAs. Then I used Dijkstra’s algorithm to search for the path of smallest energy cost to a Car at the starting location with no TAs. Conceptually, the “neighbors” of each Car involve all the possible nodes it can travel to and all the possible combinations of TAs it can drop off. The “cost” of the edge to that “neighbor” is just the cost of the drop offs and the cost to travel to that next node.

Improving performance of the algorithm was quite interesting. After optimizing the initial Python implementation as much as possible, I decided to convert it to C++. Based off some rough calculations, I reasoned that it would be barely possible to brute force the smallest size inputs we would be given, 50 nodes and 25 TAs. It took a lot of effort, a complete restart, and serious optimizations including bit manipulation and memory allocation, but I learned a lot and achieved a 100x speedup over the Python implementation. After using cProfile and Callgrind, I found that both my Python and C++ implementations probably couldn’t be improved much further, so I moved onto the rest of the project.

Sorted (sortedpython)

Even with the optimized brute force algorithm, it was still not fast enough to do anything above 16 TAs. As a first attempt at improving speed, to generate neighbors I tried sorting TAs by distance from their home and only dropping off farther TAs if I dropped off closer ones too. While an improvement over the naive solution of dropping everyone off immediately, this did not end up working too well.

Minor Improvement (minorimprove)

Thinking about the optimal solution, I reasoned that no edge is double traveled by TAs on their ways home. Also, there’s probably room to improve the cycle traveled to get to each drop off point using a TSP approximation. Based on these two observations, I wrote an algorithm that takes an existing output and improves it. However, it does rely on having a very good one already. Also, since I used Google OR-Tools there were cases where it did perform worse.

Optimized TSP (optimizedtsp, optitsp)

My teammate Joe came up with this algorithm. It’s based off the observation that dropping TAs off at their homes and using TSP to find a cycle actually works pretty well. First, he used LocalSolver’s TSP solver to find an order to drop off TAs in. To optimize further, for each TA, he’d consider all other nodes as drop off points and use the one with minimum cost. Repeating this multiple times ended getting very close to optimal for a lot of cases.

As we were working on our Semitree algorithm, I rewrote this algorithm as a subroutine. Since I didn’t want to wait a day to get a LocalSolver license, I used Google OR-Tools. Later on, I moved over to Gurobi which improved performance even more. I also added on the drop off cycle optimization from the minor improvement algorithm to further reduce cost.

ILP Reduction (gurobilp)

Talking to a bunch of HKN people, I realized that all of them used an ILP reduction for their algorithms. It was then that I learned about Gurobi, an ILP solver that’s among the best in the business. Hearing everyone keep talking about finding “provably optimal” solutions got me interested. Three nights before the deadline, I took a look at the TSP ILP reduction. A couple hours later, I had an ILP formulation.

Basically, like the TSP ILP reduction I’d have a binary variable e[i,j] for each pair of nodes, but directed instead to simplify things. There’s also binary variables for each TA for each node, called v[i,k]. I also had indicator variables for if a node is a drop off point. For the constraints, I first had to make sure each TA is dropped off and only once. Then for each drop off point, make sure we pick one edge leaving and one edge entering it. My first reduction had a couple more variables and constraints, but with some help from my teammate Kevin we got rid of them and improved performance significantly.

Semitree (semitreeTSP, semitreeILP)

My teammate Kevin came up with easily the best algorithm we had. He worked on his own implementation, but I also did my own using a different perspective of the algorithm, which I’ll explain. Basically, we’re looking for nodes whose removal splits the graph into subgraphs, which are called articulation points. We’re also looking for biconnected components, which result from removing articulation points. We generate a tree-like structure based on these points and components. From the starting location, we look at all the articulation points in each biconnected component it’s in. For each point, we look at its child subgraphs. If there’s one TA total in them, then we replace the point with a fake TA. If there’s more than one, then we replace the point with a fake TA, force a visit there, and recurse on it.

To find a solution for the resulting biconnected components, we’d employ one of our other algorithms, mainly Optimized TSP and ILP Reduction, which I modified to support forced visits. After solving subgraphs, we’d stitch together the different parts to generate the final output. This algorithm worked so well because it employed provably optimal techniques in a divide and conquer fashion to break down the problem.

Generating Outputs

In order to streamline the process of generating outputs, I setup a framework of multiple scripts to automate tedious tasks. The main one was bigsolve.py which ran a specified algorithm on certain inputs. The real benefit was that it only wrote to the output folder if the algorithm’s solution was better than the existing one. This allowed us to quickly try different modifications and algorithms without worry.

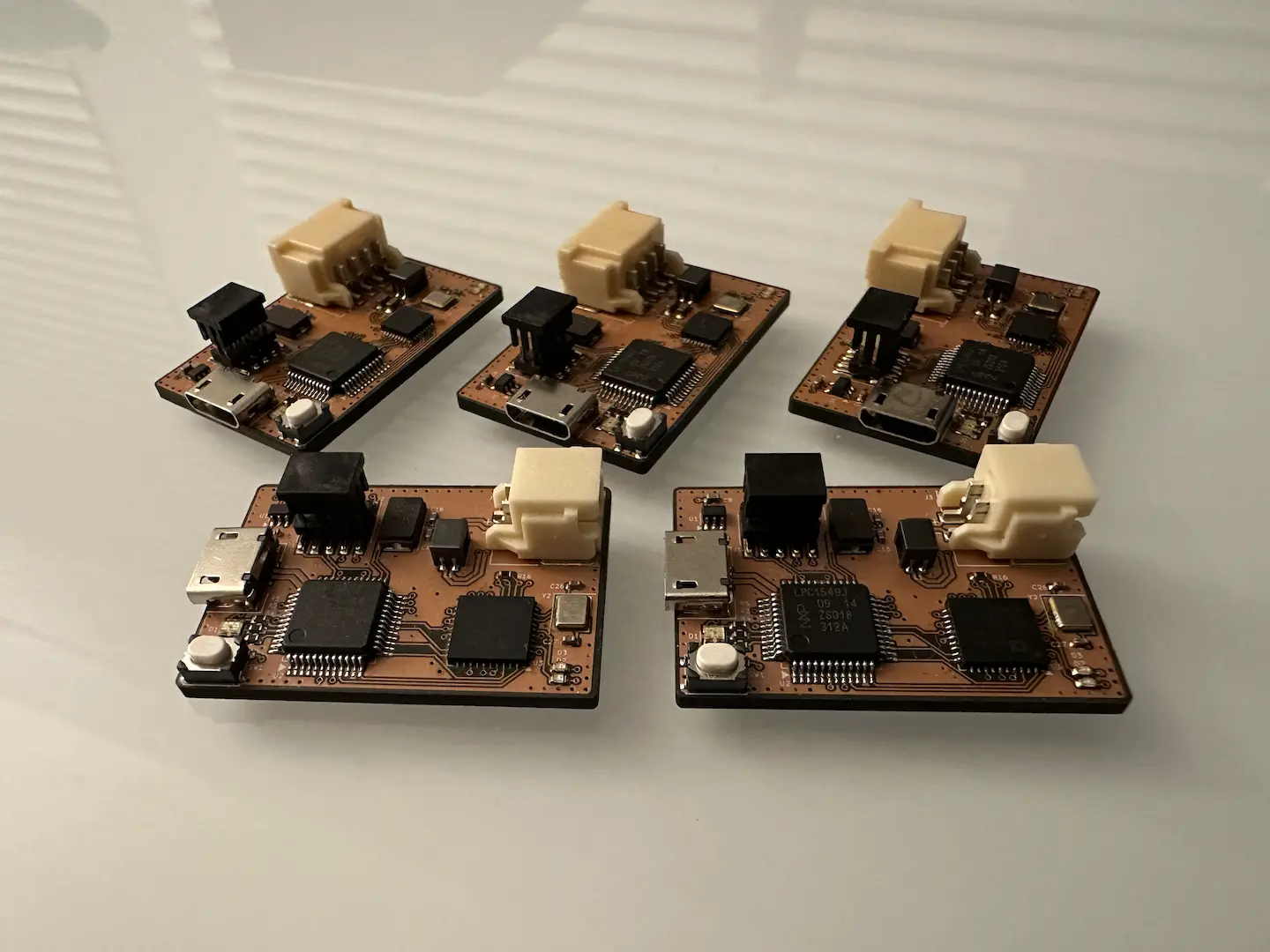

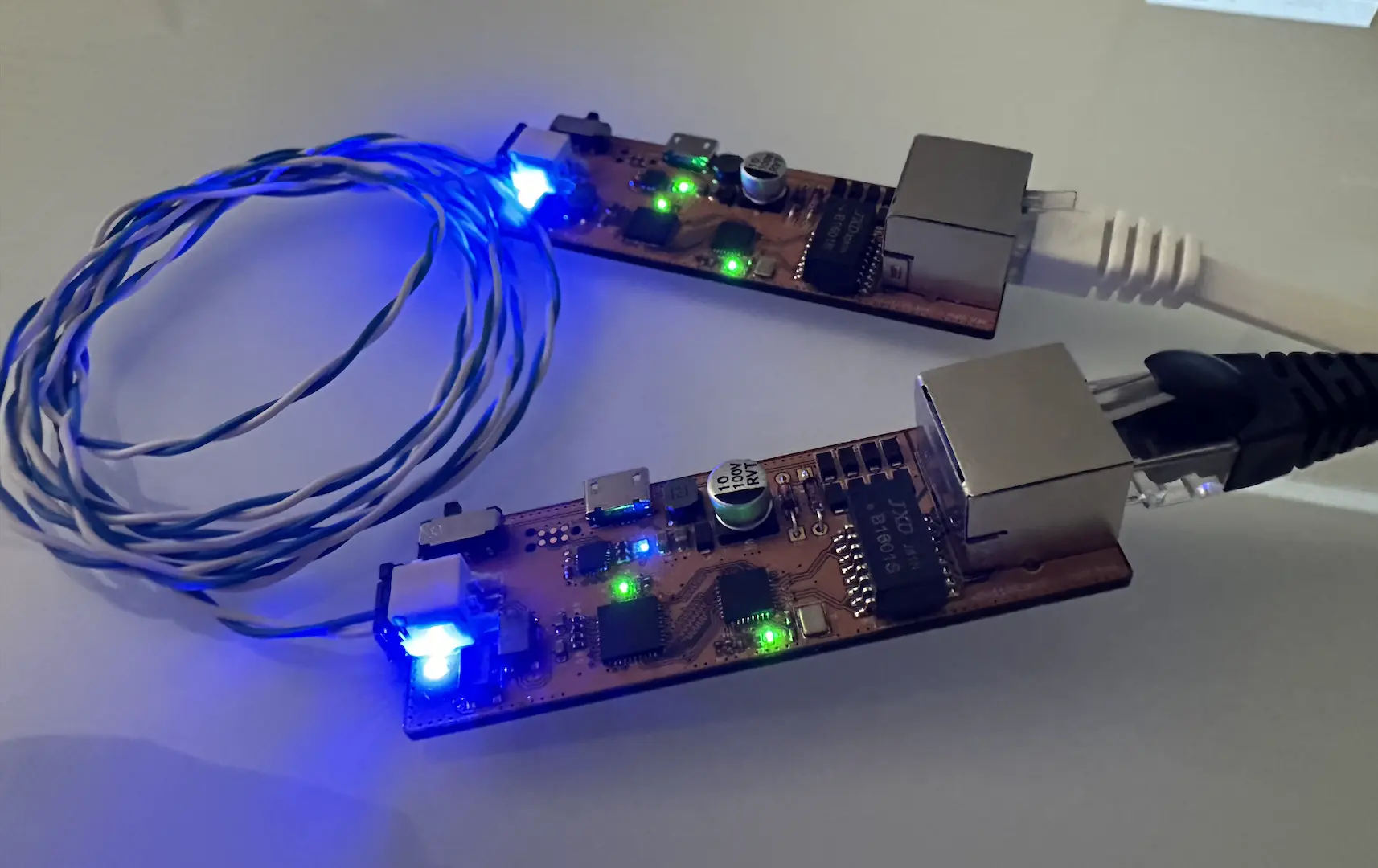

Since we found out about Gurobi less than three days to the deadline, we really had to make the most of our time. In an unfortunate turn of events, I sent my gaming computer and some Ryzen processors I bought for Black Friday home to work on during winter break. Literally the only computers we had were my 2018 Macbook Pro, Joe’s 2016 Macbook Pro, and one of the Hive machines. Luckily, due to heavy optimizations in our algorithms and good organization we were able to generate “optimal” outputs for all but about 180 inputs.

As for the breakdown of how each algorithm did, about ~80 of them were solved optimally using my brute force C++ algorithm. A good ~700 of them were solved “optimally” using semitreeILP, which used the ILP reduction as a subsolver. The rest of them had very good approximations generated using semitreeTSP, which used Optimized TSP as a subsolver. In fact, semitreeTSP could generate outputs for all 949 inputs in under an hour and was within ~2% of optimal if not optimal in most cases.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, I did not expect this project to have as much an impact on me as it did. True to my personality, I tackled it first and foremost as a software engineering problem. I setup a framework that made development and testing of the algorithms we’d develop straightforward. Comparing against the brute forced optimal solution and naive solution helped guide our efforts and led to some discoveries that inspired our best algorithms. Later on, I dived into the theory side to help come up with even better algorithms. Although our team did end up getting 5th out of about 366 teams, I really appreciated how much I learned in the process. More than anything, I really could not have done it without my teammates.

Comments