JABI (Just Another Bridge Interface)

https://github.com/dragonlock2/JABI

After developing stbridge to bind STLINK-V3-BRIDGE to Python for easy usage, I was not satisfied. The hardware and firmware of the STLINK-V3 were both closed-source which meant I couldn’t fix any bugs I found. Even the library code was under ST’s weird license. Furthermore, my retrospectively poor decision to use Boost Python to create the bindings was absolute hell to get compiling and the reason I chose not to port it to Windows.

The motivation for JABI came from wanting to build something like stbridge but fully open-source and far easier to build and use. While it wasn’t conceptually difficult, the sheer number of moving parts and things I had to learn meant the whole project took me over two weeks to complete. At the end of the day, I’m quite proud of what I built. It is easy to use and most of all maintainable.

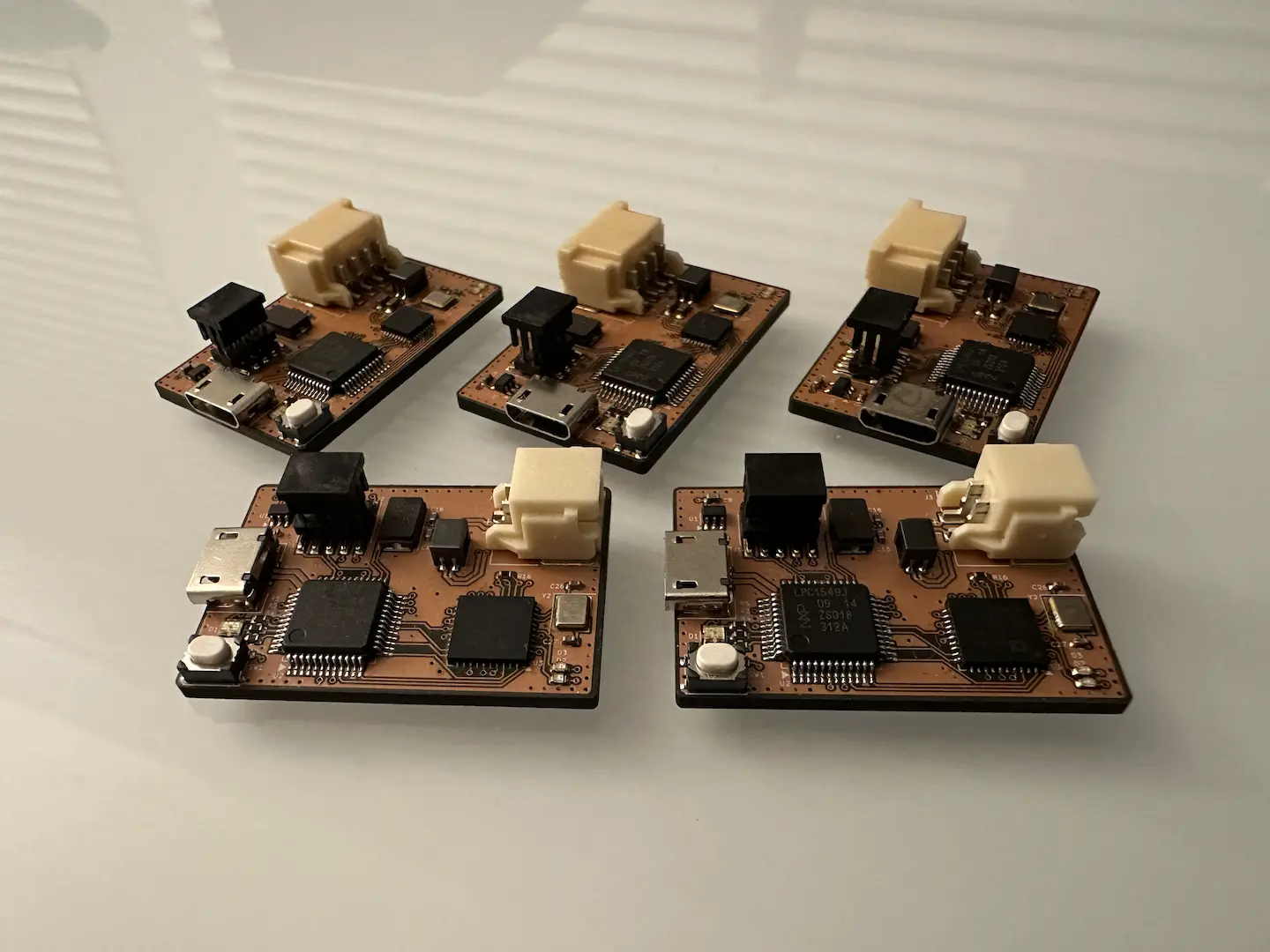

Hardware

With a global chip shortage, the last thing I wanted to do was tie JABI to a specific microcontroller as with STLINK-V3 or Bus Pirate. While with a fixed microcontroller I could tailor the performance and features more easily, in this case flexibility is far more important. The only hard requirement for a microcontroller is that it can talk to a host OS over one of the supported interfaces (ex. USB, UART). The rest of the hardware is really up to the designer.

Firmware

The key reason this whole project was even possible was Zephyr RTOS. Unlike Mbed or Arduino, Zephyr does an amazing job at cleanly separating application code from hardware specific factors. The same application can be compiled for a different board by simply naming it. If the microcontroller is already supported, porting a board using it to Zephyr – and thus JABI – takes minutes. If it’s not, it’ll take longer but the framework is set up to make it relatively straightforward.

Since Zephyr doesn’t have an RPC implementation built-in – although it appears Thrift support is being worked on – I had to design my own. The only real consideration here is the request and response packet formats which contain things like a function ID, return code, and variable length payload. To reduce the memory footprint and remove the need for dynamic memory allocation, there is also a configurable maximum length to each packet.

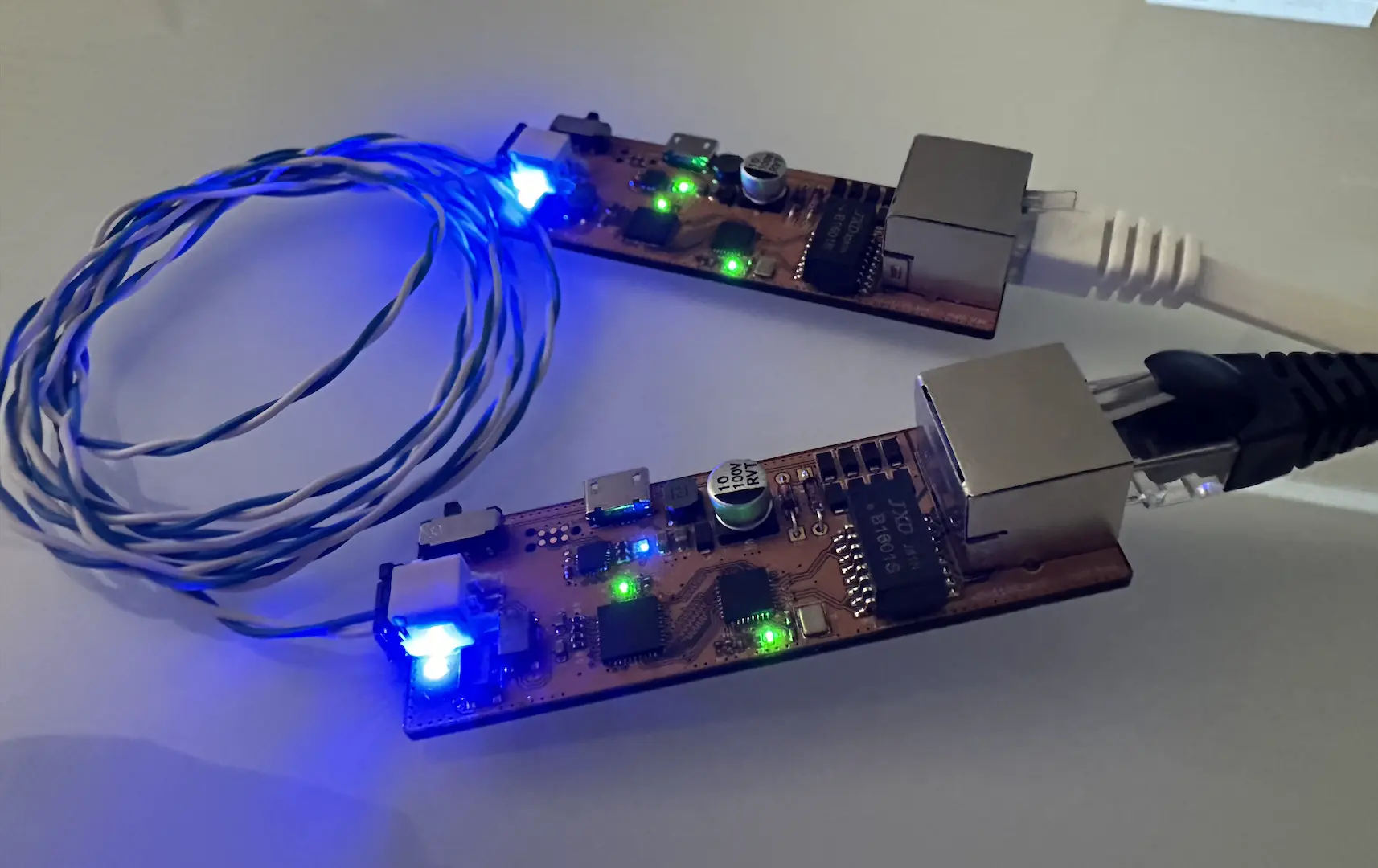

With that, each supported interface just needs to be able to send and receive the RPC packets. UART was relatively straightforward since it uses a semi-reliable byte stream. All I had to really consider was adding a timeout to ensure a bad short packet arriving now wouldn’t affect a good one later. USB was harder with its dizzying array of descriptors, but I eventually got them set up and reliable in-order bulk transfers to work.

Peripherals were even easier to add support for since for the most part they just called the underlying Zephyr API. The hardest part was balancing flexibility and ease of use when figuring out what parts of the Zephyr API to expose and how.

In order to support multiple interfaces and thus clients running concurrently, locks are added around peripheral accesses and are shared in case the same underlying peripheral instance is used. To avoid an adversarial client being able to crash the microcontroller or even worse hack it, I made sure to do a religious amount of error checking at all levels.

Software

The most annoying part of writing the software libraries was getting them to compile across macOS, Windows, and Linux. The differences between Clang, GCC, and MSVC popped up time and time again with warnings and lack of compiler support for some C++ features. Eventually, I ironed all of them out and now have a clean dependency setup and build process for each.

The first and most important library to write was the C++ one. Baffled by how annoying STLINK-V3-BRIDGE was to use, I strived to keep the interface clean at all levels. Adding it to any application involves a simple CMake add_subdirectory() call. Opening a device for use involves just calling the appropriate function from the desired interface. Accessing a peripheral is a simple function call and often times takes a single line of code. Exceptions are thrown only in fatal errors (except for maybe an I2C scan) to keep function definitions simple. Using smart pointers and locks, a device can be shared among multiple threads in case that’s needed.

While I could’ve written the Python library in pure Python, I wanted to reuse my C++ code and learn pybind11. It ended up being surprisingly easy to setup and get running and I could get bindings up in minutes. Since I didn’t want to have to be in a certain directory or manually copy files to install it, I made the Python library locally installable and manageable using pip. It even works in a Python virtual environment!

To bridge JABI to a network using an industry standard RPC framework, I decided to also write a gRPC server binding the C++ library. I even wrote an example client which provides the same interface as the C++ library but only depends on the protobuf file. The gRPC server may one day pave the road to mobile apps or Web interfaces.

Comments