Hovercraft 2017

Written 9-14-19

An interesting event that came in during the SciOly 2017 season was Hovercraft. The engineering portion of the event involves building a hovercraft that has a mass of 2kg and can travel a certain distance in a certain amount of time.

v1

Seeing as the biggest source of points for the hovercraft came from being 2kg, I tackled that issue first. To begin putting together a design, I started by researching the physics behind hovercraft. I won’t go into too much detail, but the gist is that air from a motor with attached propeller/impeller is redirected out to the perimeter of the base downward, lifting the hovercraft. Air is trapped underneath the hovercraft as it lifts and is kept there by the fast moving air around the edges. A skirt helps improve lift, hover height, and stability.

The main restriction in the rules involves only being able to use two brushed motors. Technically, brushless motors were allowed in the form of cooling fans, but finding one powerful enough would’ve been a challenge. It’s also more fun designing a custom lift system. If I remember correctly, there’s an 18cm diameter limit to propellers and they had to be shielded with 1/4″ holes. The base hovercraft size was limited to about 20cmx30cm. With these design requirements in mind, I got to work.

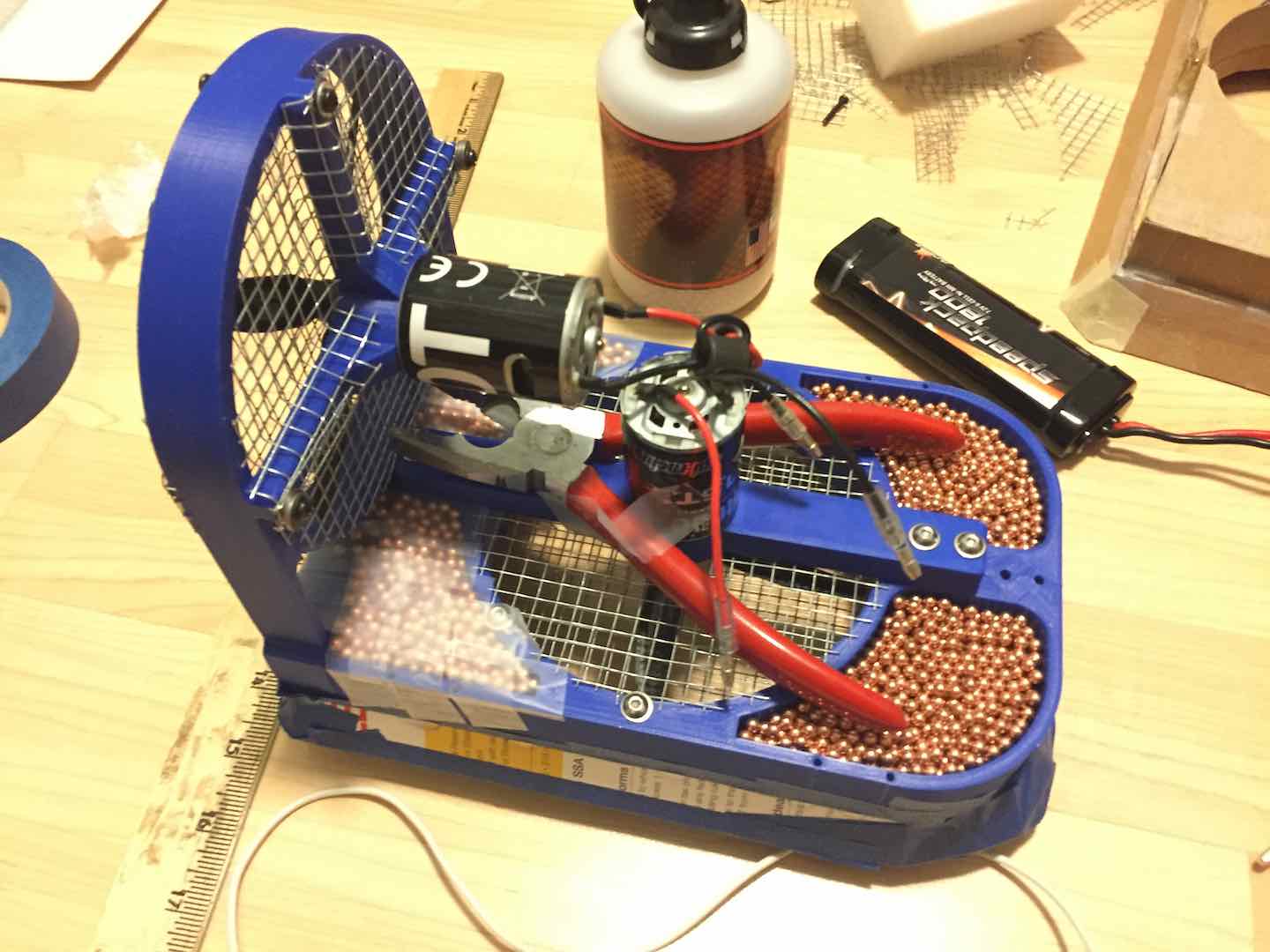

I had only just gotten started in CAD and 3D printing so my design was bulky and not particularly well thought out, but it worked. After printing it out, I slapped on some motors, shielding, and steel BB weights and got to testing. Eventually after a bunch of testing and stacking two 4 blade propellers to make an 8 blade one, I got the hovercraft to lift its mass of 2kg.

Easily the biggest issue with this design was its inefficiency. The motor drew around 80A and burned out rather quickly. It was also incredibly loud and barely produced enough lift for 2kg. Also since it hovered about 0.5mm off the ground, there was effectively zero friction, making it harder to control.

v2

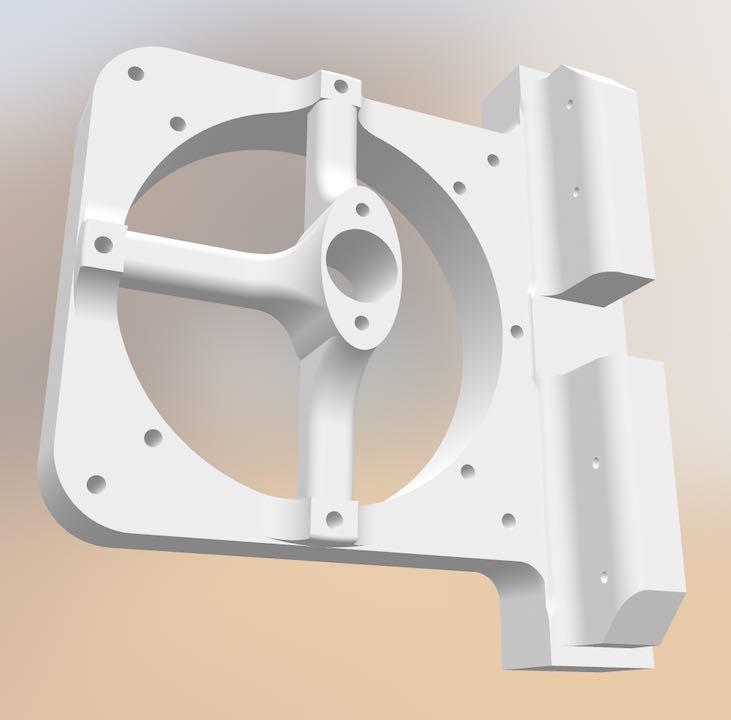

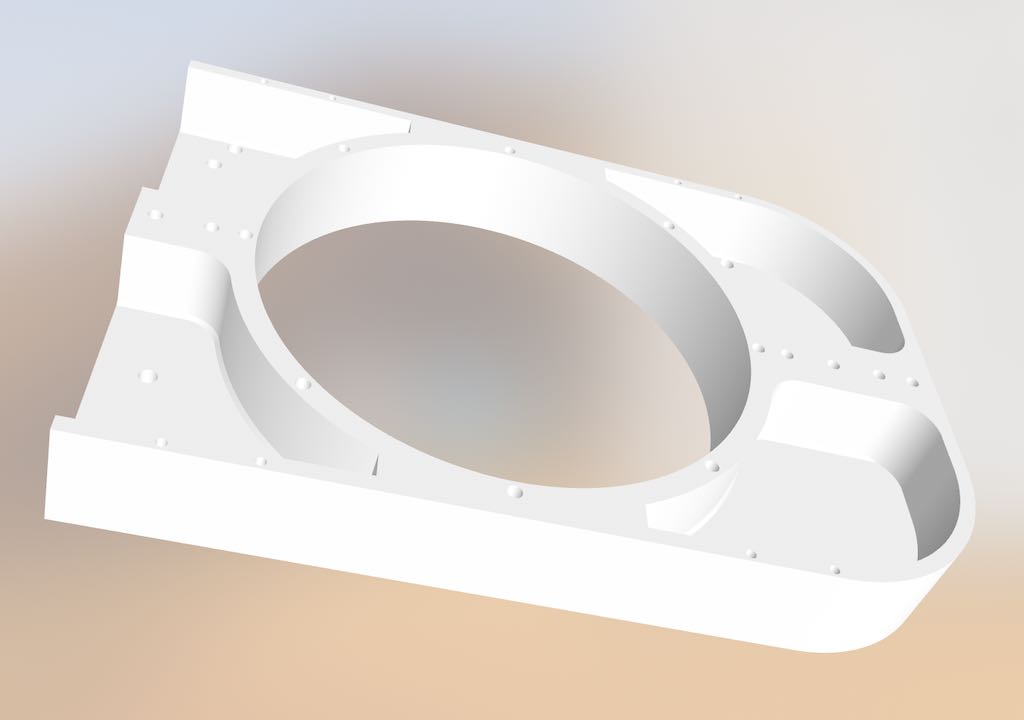

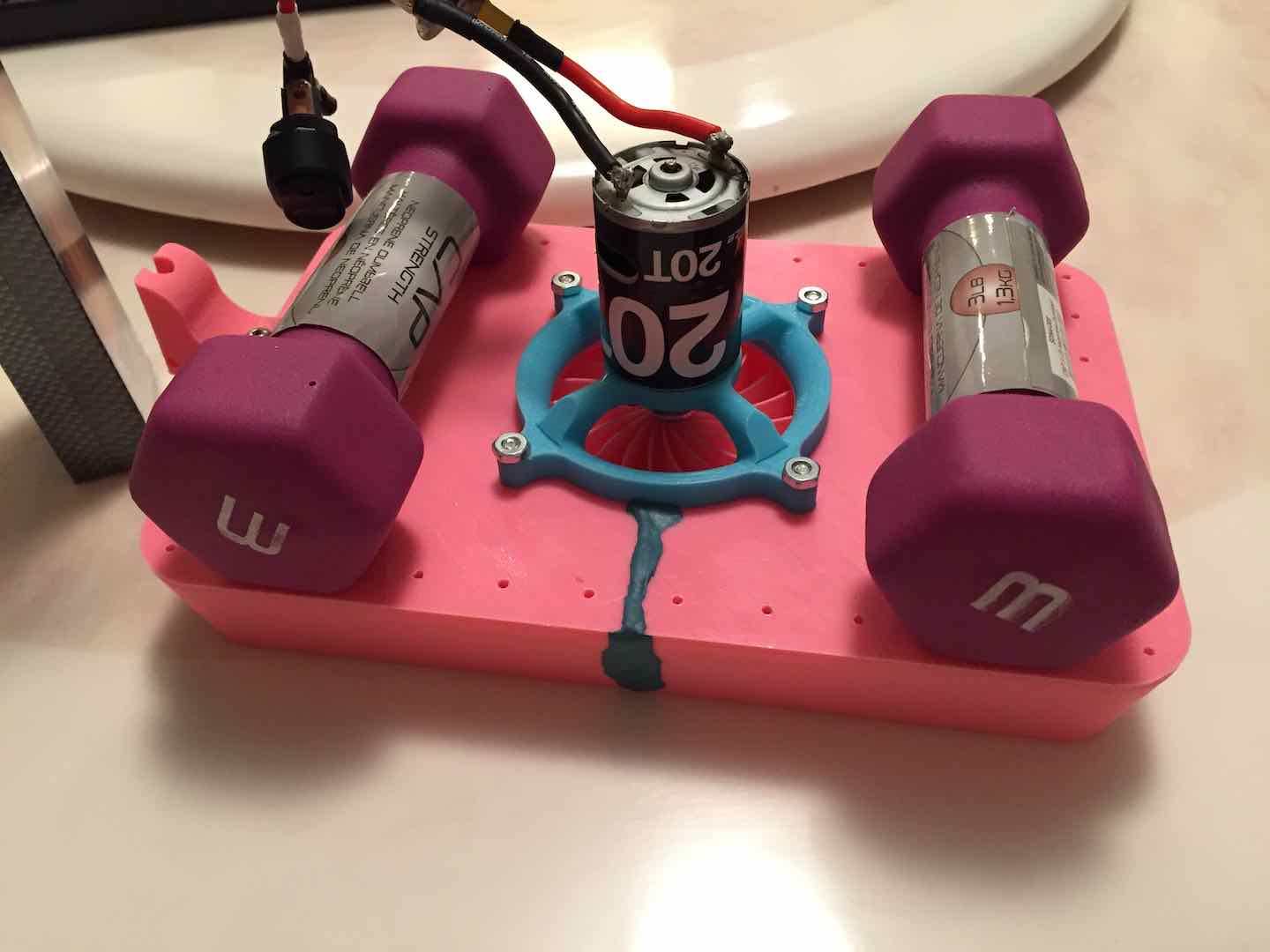

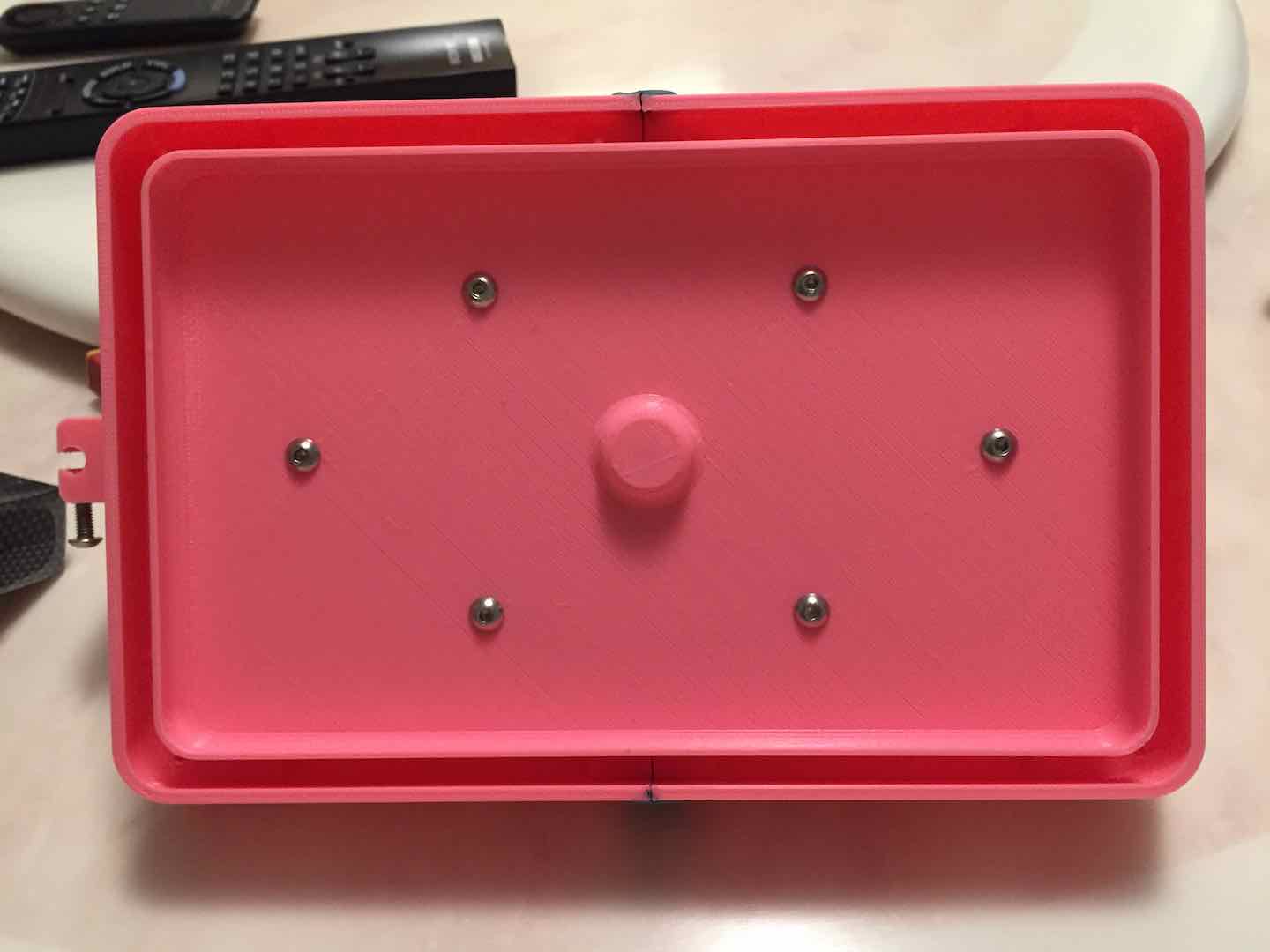

Seeing how poorly v1 performed, once I had enough time I immediately got to working on a new design. This time I used actual designs for real hovercraft with air redirected around the edges and a skirt. I also switched from an axial propeller to a centrifugal impeller. Propellers are good for things like helicopters because they can move a lot of air at a high velocity but perform poorly in a relatively enclosed area with a lot of back pressure. Centrifugal fans perform well in these situations. The CAD files are all over the place, so here’s some half assembled pics.

The impeller design was surprisingly straightforward. I tried a bunch of different combinations of number of fins, diameter, curvature, and angle in order to optimize lift and current draw. Eventually I settled on something like this.

After getting the hovercraft to lift its 2kg efficiently, I started working on all the add ons to do the rest of the event.

Skirt

Although the hovercraft was effectively frictionless already, the hover height was barely perceptible. One of the rules is that to be considered hovering one must be able to press down on one side, let go, and see it rise back up. A 0.1mm gap is very hard to see, so I got to work on a skirt. Using some Tyvek, I put together a very basic skirt to get hover height to about 15mm. I was actually looking for ripstop nylon, but I bought the wrong material. This also had the side effect of making weight balancing much more tolerant and increasing friction with the ground.

Timer Circuit

Easily the most difficult part of the event was the timing. If I remember correctly, we had to make the hovercraft travel somewhere between 1-2m in 5-25s. The exact distance and time would be revealed at competition. Since hovercraft are effectively frictionless, this made it really hard to be able to adjust the forward thrust to achieve such times. I also had to keep in mind that the hovercraft had to not stop for more than 3 seconds at a time. Even more, microcontrollers weren’t allowed, only pure transistor logic.

My basic idea was to make the hovercraft oscillate around the starting position and then after a certain amount of time, it would move forward at top speed. After a ton of experimenting with H-bridges, I gave up on the idea of having the thruster go forward and reverse. Eventually, I noticed that friction on the bottom of the hovercraft and the side rails were actually enough to stop the hovercraft given a small starting velocity. This gave me my eureka moment where I realized that I only needed to pulse the thruster forward once every 3 seconds (2.5 to be safe) to keep the hovercraft moving. Friction would stop it between pulses.

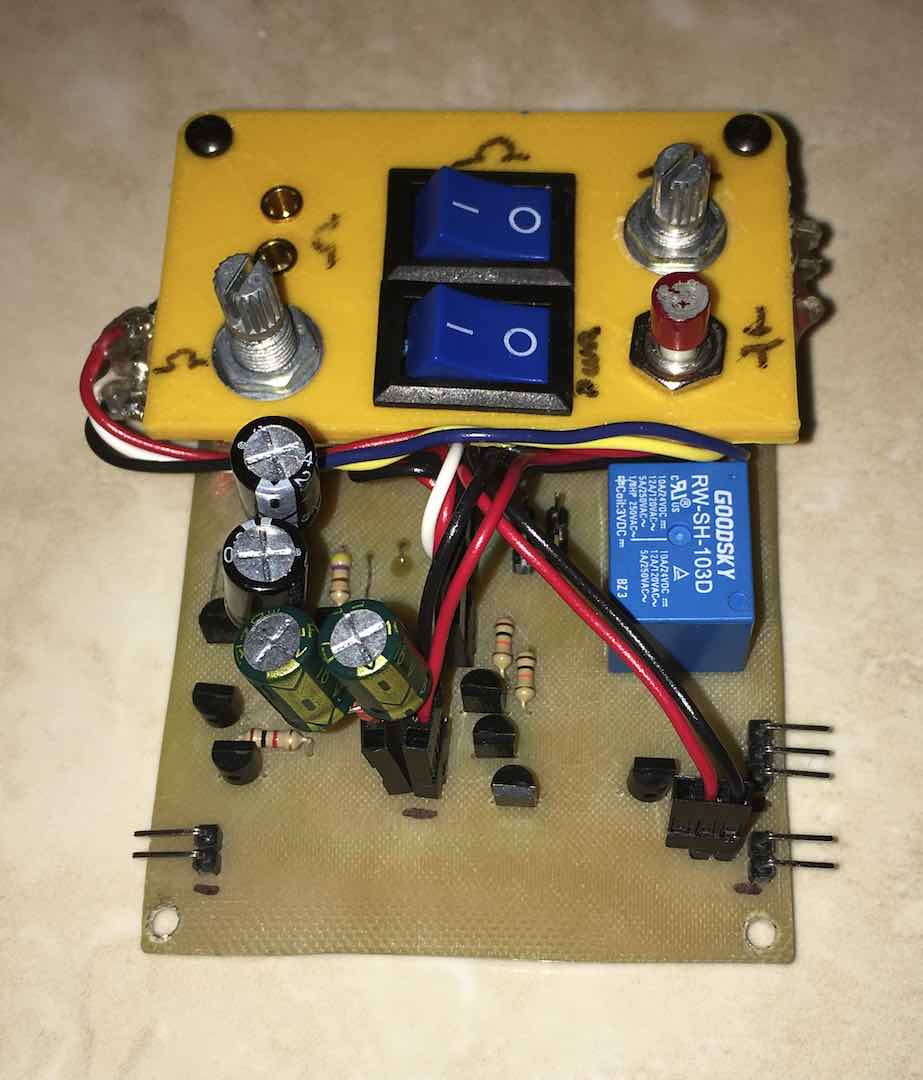

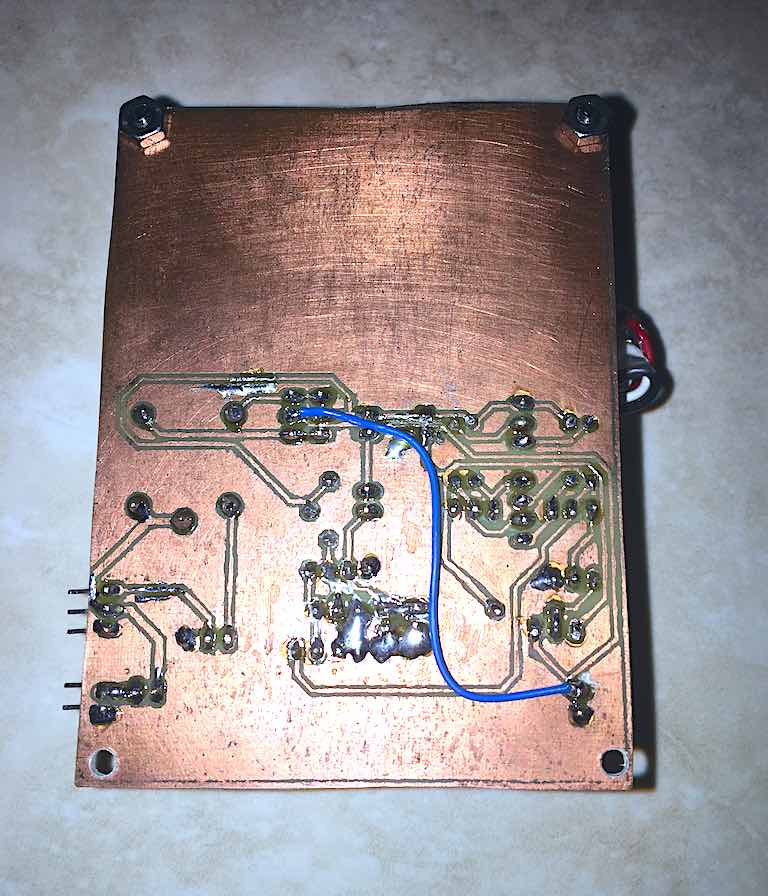

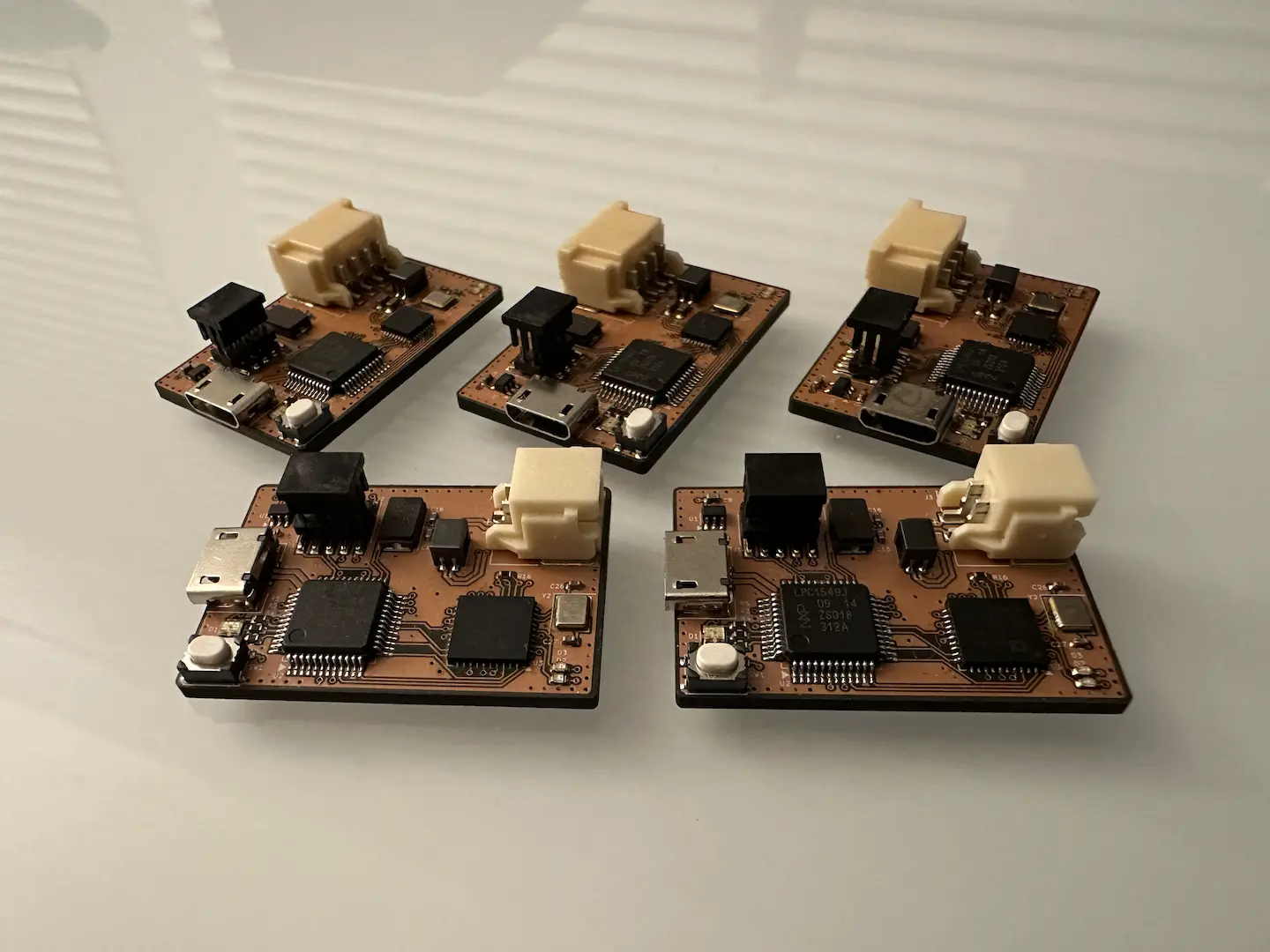

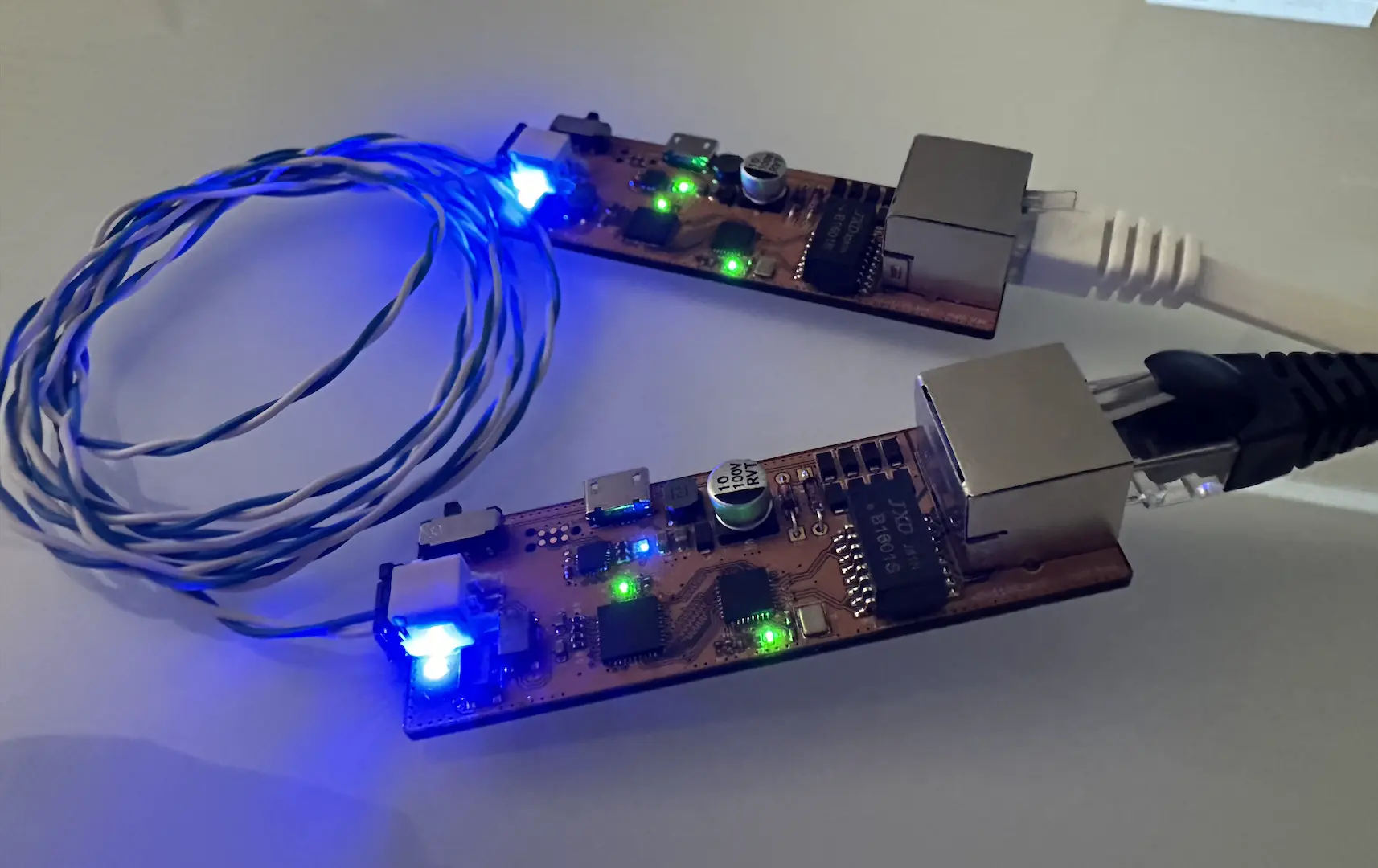

To implement my idea, I learned about astable multivibrators since ICs weren’t allowed. I also designed a delayed pulse generator to turn on the motor after a designated amount of time. What’s really cool was that I got to apply my knowledge of RC circuits from Physics 2 to calculate the correct resistor and capacitor values. I made a prototype on perfboard and later used EAGLE to design a PCB which I made, with barely any success, using the toner transfer method with a clothing iron.

I don’t remember why I used a relay because I used a MOSFET elsewhere to do the motor switching, but it was probably because I didn’t know enough about transistor logic at the time. On the other hand, the circuit did work perfectly.

Front Switch

While competing at the state competition at CalTech, I was devastated to see that my design malfunctioned. The timer circuit wasn’t turning on. Immediately following competition, I figured out the issue. In order to determine when to start the timer, I used an IR sensor at the front to see when the starting block was removed. In almost all conditions, including outdoors, the sensor functioned perfectly. However, in the specific room that was used for competition, there must’ve been an excess in 900nm IR light or something because the front sensor wasn’t working.

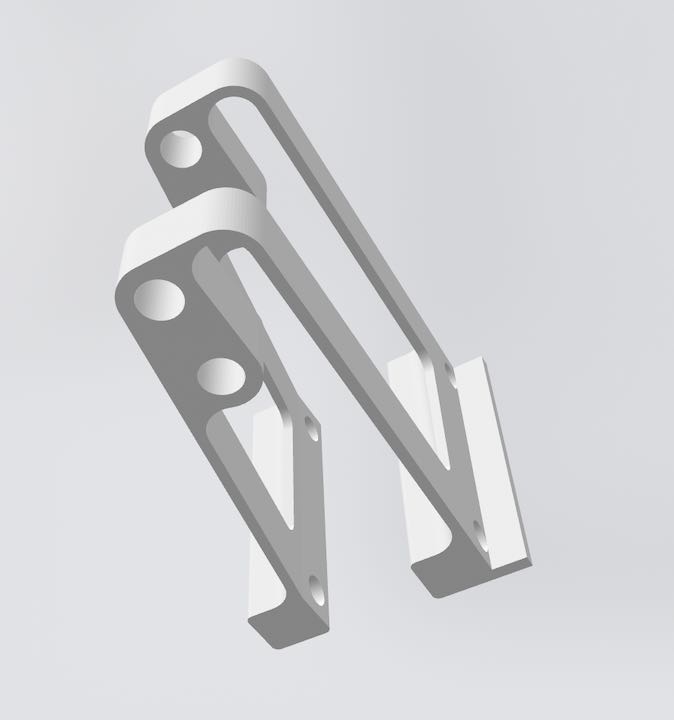

In order to ensure this problem would never show up again, I decided to design a mechanical switch to replace the IR sensor. To guarantee that the hovercraft would pass the starting line, which is when timing starts, when the starting block is removed, I made the thruster go full power forward when the block is in front. Propeller inertia would provide a bit of initial thrust. This meant that the front switch had to have a very low actuation force. Doing measurements, I determined it had to be in the range of <50g. For fun and also because I didn’t want to find and buy a matching switch, I designed my own.

The switch made setup a little bit harder but I never ran into the IR issue ever again. To this day I still want to revisit that room at CalTech with an IR camera to figure out what happened.

Competition

At nationals, my design worked absolutely perfectly. It was about 0.2s off which was as good as I could reasonably expect. I don’t remember anyone else having quite as clever a design, but since the concept is relatively simple I’m pretty sure other people independently came up with the same design themselves too. After doing my run, one of the proctors shook my hand because of my design. I was pretty happy about it at the time because before I didn’t think what I did was that impressive. Later on, I realized that the proctor that shook my hand was actually Dr. Gerard Putz, cofounder of SciOly!

What’s pretty cool is that Mr. Wahl, my head coach for SciOly and amazing teacher, actually used this video of my hovercraft to teach applications of RC circuits in future Physics 2 classes.

Comments